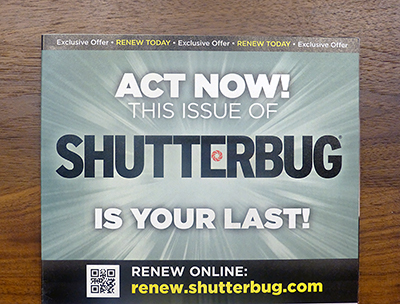

This Is Your Last Issue

A little under two years into the subscription, a couple months before my birthday, I received a renewal for Shutterbug similar to the one pictured above. I went online and dutifully extended the subscription for another two years. It had, after all, provided me with loads of practical photographic advice about lighting, various filters and techniques for shooting different subjects, and generally been worth the relatively trivial $24 or whatever it cost.

The original subscription had been a birthday gift from my father back in 2008. Photography was something we’d always shared a common bond around, and since he got just about every trade mag, it was a logical way for us to share topical conversation on a monthly basis.

He had been quite a prolific photographer in his twenties and thirties, demonstrating a natural talent for capturing the mood of an incredibly diverse portfolio of subjects as well as the skill required for extracting maximum impact in the darkroom. Over the years, I’d soaked up some of this knowledge, logging time in his darkroom myself as I worked on projects in high school and college. My eye for composition was not nearly as keen as his, but showed gradual progress (when I wasn’t being dismissive of his advice).

In the years after I moved to California we were always able to slide easily into discussions around photography, despite the physical, and emotional, distance. Dad always perusing the listings for functional used equipment, and I always trying to find filmic quality in the newly emergent digital market.

One thing we always came back to, regardless of where the market was headed, was technique.

At some point I discovered Ansel Adams’ core trilogy, and attempted to show dad how literate I was by dropping references to the Zone System and underexposing in the camera so you could bring out highlights in the darkroom.

When I extended my subscription it had been just a few months since my father had died. I hadn’t thought about the magazine at all really in the months since, largely because I had held the mail while I was helping mom back at her home.

Seeing the renewal notice caused a fresh wave of anxiety, grief and panic to wash over me. I couldn’t let this precious tie to my father disappear, not when it was so easy to maintain.

It was a bridge to the past, to happier times when we spoke to each other as adults, not as a father and son. We were—if not precisely equals—on common ground.

Photography was perhaps the only field where our dialogue was just that, dialogue. It was a discipline where we could discuss something that, while founded in science and practical application, was just as subjective as anything I had studied in art and architecture. Indeed, the more accomplished you become at the fundamentals of making a good photograph, the more capable you are of artistic expression through the medium.

Photography was a pursuit where dad’s rules, compulsions and inability to accept being wrong, grudgingly gave way to artistic interpretation. For all his OCD, he could not control what others liked.

In retrospect, I realize, sadly, that photography was perhaps the one aspect of his life where he felt comfortable expressing feelings. It was a way for him to accept his emotion, get it out of himself, let others see it, without allowing it to affect him, to compromise the integrity of the walls he’d built around his own feelings.

When mom decided to move out of our childhood home, Steve, my aunt and I, all took turns coming through the house to help her pack up what she would take with her and sell, donate or otherwise dispose of things she no longer needed.

Dad had amassed quite an extensive collection of gear. I packed up a camera or two, some lenses, one of the enlargers and his drum developer system. Steve took some of the gear as well, and the rest either got sold cheap or given away to folks in a yard sale.

As I went through the shelves in his darkroom, also home to most of his books, I found a copy of Adams’ books. I laughed out loud as I thought back to dad listening to me ramble on about zones and post-shooting enhancements all those years ago, nodding along as if I’d uncovered some ancient tablet that held heretofore unknown secrets of great photography.

All at once, the brash, arrogant exuberance of youth presented itself, visible now in hindsight. How often, I wondered, had dad shown a practiced look of surprise or interest as opposed to a more genuine response to actually new information? Did it matter? In the eye of the beholder, was there a difference?

Over the next two years the distance from dad’s passing steadily grew. It became easier to observe the anniversary of his passing, and his birthday which was just three days after. The anxieties decreased and life went on.

Then the issue pictured above arrived in the mail.

It hit my heart like a speeding freight train, knocking the wind right out of me. Over the previous twenty-three months I had gradually stopped reading NAME, and it had been well over a year since I had picked up a camera that wasn’t part of my phone. Just then, all the memories flooded back.

But something had changed.

I was no longer compelled to keep the conversation going. I no longer felt like I’d be letting dad down if I didn’t renew the subscription.

It might be that I realized the best way to honor dad was to focus on Leo, not the past. It might be that I had started to question my own interests as an extension of my dad’s. It might be that I believed he’d moved on to his own new life and that it was selfish on my part to hold him to his old one. It might be that to transport myself back to our conversation was to open myself up to the pain and feelings of inadequacy I experienced, largely unaware, as I grew up.

It’s probably for all of those reasons, and countless more, that I knew I had to let the subscription lapse. That to move forward, I had to let go.

Now that Leo is older and in elementary school, I find myself in my father’s shoes. There is a distinct age when children begin to learn things from others, their peers or their teachers, and from their own books or the internet. An age when you, the parent, are no longer the primary source of new information.

It is at that age that it smacks you right in the noggin: you are in your parents’ position. You must allow your children their opinions and views, right or wrong, so they can learn to draw their own conclusions from experience and evidence. You must allow them to present you with their learnings.

You must accept that they have “discovered” Ansel Adams.

For me, this was as happy a moment. Happy for the fact that I was alive to appreciate what a wonderful human being Leo is. Happy that he is a capable, intelligent person, asking questions and learning to learn. Happy that I had the good fortune to learn this lesson seemingly early in Leo’s life, that I may be more supportive of his growth. Happy for realizing that I am free to experience every moment with him completely in the present. Happy for the very gift of life.

It was also singularly difficult. It is the precise moment when I concretely realized I must prepare yourself for the greatest letting-go of all.

A Postscript

We can never be sure what our own “last issue” will look like, so we must always strive to make every experience matter. We should treat every experience with a level of respect and openness, with a degree of novelty and wonder that a child might.

That’s not to say that we must derive happiness or positivity in every moment. An argument, a difference of opinion, a loss or tragedy are all be sources of inspiration and growth.

We should live life trying to infuse every interaction with meaning, for others far more than for ourselves. We should seek to enrich the lives of others with every shared experience, whether through direct action or indirect influence. To paraphrase the signs at every campsite, we should leave other’s lives better than we found them.