John

Maybe we can’t feel complete until we know enough to tell our stories. But learning our stories isn’t something we can do alone.

—David Kushner

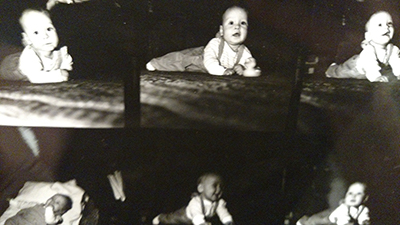

A few years ago, I found this photo slipped into some things I had packed from my childhood home. No doubt my mother had tucked it away for me to find at some later date. The discovery came as a bit of a surprise because for as long as I can recall it was housed, unmoving, in a frame in our living room.

The room itself was a dismal shade of yellow, with a sofa and chairs to match. It was a room we rarely used, full of old books, antiques and other photographs of elder members of the family that spanned the better part of the twentieth century. A truly cavernous fireplace seemed to actively suck any daylight into its blackened chimney, and the tobacco-lined lampshades only added to the overall pallor of the atmosphere. It was, to put it mildly, not a room you’d want to spend any decent amount of time in.

In that room, when I first noticed the photo of John and my father, I was taken by it immediately. The frame was folded like an open book, and on the side opposite this photo was one of my mother smiling broadly, long golden hair flying about in a stiff breeze.

They were all so happy, so carefree, it was impossible not to smile along with them when you looked at it.

In the hallway, just outside my parents bedroom, there once hung an unassuming needlepoint in a blueish wooden frame. The most prominent part of the design was a restful, smiling, fair-haired baby boy, beneath which was a name, John Chapin Listwon, and the date of his birth.

It was the type of handmade gift you might find in any home around the world; a gift received from a crafting-inclined relative celebrating a new addition to the family.

For all intents and purposes it was unremarkable, save one detail: it also bore the date of the John’s death.

I’m not totally certain at what age I first noticed the needlepoint. What I do remember is when I first made the connection between the John mentioned in its tidy stitching, and the photo in the living room.

I was seven at the time and had gone into the living room to put away a game we had just been playing. (We kept our board games in some cabinets beneath the shelves on which the photo was displayed.) For one reason or another, as I set down the game box and repacked the cabinet, it just clicked.

I didn’t know what to do with this information.

In the year that followed, as I passed the needlepoint, I made one of those idalistic, but well-intentioned childhood resolutions to wish John a happy birthday with each passing year. I did so in my head for the first couple of years, keeping the practice to myself.

As I got older I found I had more that I wanted to share with John, but felt awkward about it. Just opposite the needlepoint was the door to our attic, a suprisingly roomy affair that ran the length of the house. Over the years I had started to spend more and more time up there, building “secret projects,” reading or just hiding out. Fromt hen on, to mark John’s birthday, I would sit just behind the door and share my thoughts with him.

In effect, he had begun to fulfill his role of older brother, a role he’d never been able to assume in real life. He was a confidant and secret pen pal of sorts. Someone who listened without judgement and allowed you the time and space to think things through.

I’ve no idea if I ever shared this with my parents. I don’t know if I somehow realized it would have been tough for them to know, or if I’d just kept it to myself for fear they’d think I was not well.

It wasn’t until high school that any sort of awkwardness around not knowing John’s story became apparent. We’d just completed reading a novel in our English class—I can’t remember which—and the writing assignment that followed was to explore our own immediate family history as it related to the book.

As I thought about what to write, I struggled with whether I was in fact the eldest or the middle child in my family, whether to write about John or not.

Was it dishonest to include him having not known him? What was appropriate? How did I even feel about John? How would I write about my parents, who had never spoken of him?

For a day or two, I tried to write as if I was the middle child, the second child. But as I turned over all my childhood stories in my head, it became clear that there was no way to easily write in John’s influence on those situations. Too much explanation was required, and I felt both frustration and guilt as if I were appropriating something that was not my own.

In the end I wrote only about my own relationship with my father and grandfather. It was only then that I realized how little I knew about John, and how little my family discussed him or his brief life. In fact, I could not think of a time when we had mentioned his name in the decade and a half leading up to that point.

High school wrapped up and it was time for graduation. The morning of the commencement ceremony, holding my hands, my mother had said, “Your father is so proud of you. He’s waited for this day for … a long time.”

Though I didn’t realize it at the time, it was that brief pause in her voice that spoke volumes about their loss.

In the years to come I wouldn’t think about John all that much. Just about the only time that stands out is a conversation I had with one of my closest friends. One night, she asked about my brother. She was referring to my younger brother Steve, who I had mentioned a couple of times, but the question tripped me up for a second.

Noticing my hesitation, she asked if anything was wrong. As I shared what I was thinking about, I realized I lacked all kinds of detail one would normally have about something so fundamental. At the time, I think I coyly redirected the conversation by attributing his death to SIDS and from then on this kind of became my go-to answer whenever people got close enough to ask about John.

When I did think about him, I wasn’t able to pinpoint why my family didn’t discuss John, his brief life, or his death. Was it avoidance, reluctance, guilt, embarrassment, fear, sadness, all of these or something else entirely that I was unaware of.

I’m pretty shitty at picking up subtlety, and so resigned myself to the fact that it was something I was missing, or some external cue I was giving off. This led to a lot of doubt and guilt on my part. Were my own actions making others uncomfortable, incapable of sharing, of opening up to me?

All of this sort of piled onto itself over the years, compounding the lack of clarity around John’s life and death, and increasing the sensation that I was somehow unworthy of the full story, that this was something my parents didn’t feel comfortable releasing into my care.

That all changed years later.

In the thirty-four years of life that I shared with my father I only twice saw him express an emotion resembling sadness. The first after the loss of his mother, the other I will come back to below.

He was capable of great anger (he once shouldered Steve’s bedroom door off its hinges because we were avoiding him), uncontrollable happiness (mostly at the expense of others’ misadventures) and a few other extreme emotions, but sadness was decidedly not on the menu. At least publicly.

So it was with a large degree of astonishment that I sat late one evening and listened to dad, turned visibly inward with his thoughts, telling me the story of what happened after John’s death.

Kiffen and I had just gotten engaged, and our typical late night conversation veered towards discussions of making choices for life and the significance of commitment to another human being.

Then he just dove in.

John’s passing, he began, hit my mother terribly. She became extremely depressed, spending days and weeks in bed. Dad continued to work, preferring to occupy his time and thoughts with external concerns, but would return home each day to a house and a wife under a very black cloud. Mom alternately refused to eat or devoured whatever food was in sight. Over time mom’s depression took hold, and her temperament would vary as wildly as her appetite.

As a psychologist all of thie must have been extremely challenging for dad, bordering on Shakespearean levels of tragic irony. Every day going to work to help others with their own challenges, yet unable to work through those at home and in his own life. Having battled with my own depression and loss, I can still only barely begin to imagine the feelings of helplessness, guilt and sadness that gripped them both.

Somehow, they managed to emerge from this very dark period. My father never losing sight of helping them get through it together, and my mother seeing in him, in them, that the were stronger as a team.

Obviously they emerged stronger, strong enough to go on to have two more children despite their tragic loss, and to raise them both to adulthood. As a father myself, I shudder to think what such a loss would be like, and marvel at their courage and perseverance.

Still … after all that, I later realized, I had no knowledge of how John had actually passed.

In January 2011, dad died.

The family gathered back in Massachusetts. We mourned. We celebrated life. We shared memories, shared meals and shared hugs. We had highs and we had lows.

Kiffen and Leo had been unable to join me right away, for the funeral, but we all returned a few weeks later to help mom get on with things around the house, and so she wouldn’t be on her own. We rotated through town, my aunt, Steve and I, spending time with mom, and helping clean out the house for her to sell.

One night, after everyone else had gone to bed, Kiffen told me, “I know how John died.” I was shocked.

She had been talking with Barbara, dad’s sister, when Barb suddenly just shared John’s story.

You’ve no doubt seen these tags on the blinds in your home or office. You probably pay them about as much heed as you do with the tag on you mattress or the airbag warnings on you car’s sun visor. If you are a parent—after about 1985—then you may be more sensitive to them, or even have learned about such dangers in a parenting class.

In 1974 though, there were no such warnings.

One afternoon, when John was having a nap in his crib, one of my parents—I’m not sure which—heard a noise from the nursery. John had become ensnared in the cords of the window blinds and strangled to death.

As Kiffen told me the story, it hit harder than even my father’s death had. Or perhaps they were compounding each other. Suddenly, hundreds of things fell into place, all at once, in a huge avalanche of emotion, understanding, compassion and empathy.

- Every window in our house had had roll up shades or nothing at all.

- Mom never let me help vacuum until I was eight or ten.

- Once, when my dad had accidentally, but deeply, cut my knee with a shovel, he was inexplicably (at the time) over-concerned with my well being. This is the second time I saw him sad to the point of showing emotion. (Promised I’d come back to it.)

- When I was three, I flew off the couch and cracked my head into our stone hearth, causing a trip to the ER. I don’t remember much, but I do remember the tension and fear on their faces.

- When Leo was born, on one visit, my dad had silently cut the loop on every blind cord in the house we were living in at the time. Something I wouldn’t notice until we moved out, and never pieced together until I heard this story.

So many countless other things. It was my own personal, cinematic big reveal, like at the end of The Usual Suspects.

As a new parent (at the time), and as the adult son of parents who had suffered such a loss, whole parts of my brain rewired themselves as I sat with this revelation.

The most significant change? A vast, profound new respect for my parents’ dedication, sacrifice and commitment to all their children, and to each other.

The existence of this story owes much to a few different inspiring folks. I struggled with even telling this story, but when I saw the way others had been able to grapple with similar situations, I felt more confident. (Mind you, it took almost two years to allow myself to write it down.)

Here’s a couple that tackle a similar loss, and the feelings, emotions and the unending ways we bump up against the myth and reality of loss as we age.

- Personal Histories by Sara Wachter-Boettcher relates a similar experience confronting the loss of a sibling, unexpectedly brought on by seemingly harmless daily interaction.

- The day my brother was taken by David Kushner, from which the opening quotation is taken, is a story about the search for truth in the mystery of his brother’s brutal murder.